Here we are in a new year, and the start of 2023 seems like the right time for a discussion about health and fitness… of the Open Access (OA) landscape.

Back in 2021, OASPA brought together people from different stakeholder groups across scholarly communications to consider how best to enable a healthy landscape with greater diversity in the economic system that supports open access publishing.

Reflections from this work in September 2021 distilled things down to three areas of focus for OASPA:

- Strengthening community representation in publishing governance;

- Developing responsible behaviour in the OA marketplace;

- Supporting efforts to transform researcher assessment and evaluation.

After getting to this point, OASPA felt that a greater diversity of views, and particularly more views from outside of Europe, were needed to balance our thinking and guide next steps.

I joined OASPA in the summer of 2022. Considering the point of representation, and the need to reflect a greater diversity of viewpoints, particularly from those outside of Europe, I’ve been gathering non-European perspectives on the ‘OA market’ work done so far.

I had email conversations and in-person conversations via Zoom with 15 individuals. All participants were asked to review the work completed by OASPA in 2021 (as documented in the issue brief and reflections). Feedback was specifically sought about the ‘OA market’ and the three areas of focus outlined above.

Whose voices?

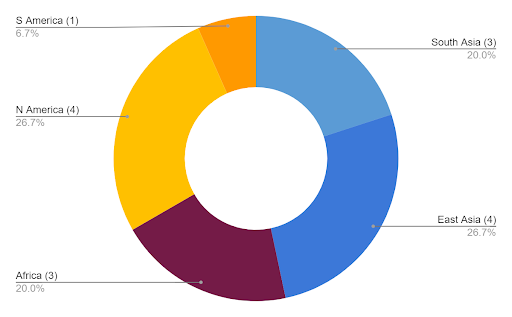

I should note how gracious and helpful participants have been with their time and their thoughts. The chart below shows the spread of world regions represented in the conversations. The individuals themselves are acknowledged in a table at the end of this post.

Views gathered in a couple of conversations cannot speak for a whole region, country or continent. The point of this exercise was not to hit a specific target number of participants, but to gain high quality input from detailed 1:1 engagement with stakeholders in regions that were under-represented in the initial work done on the ‘OA market’. OASPA specifically wished to learn more about what is felt by those in different parts of the world. Despite considerable effort, there was an overall European weighting to views documented in 2021, and so, the purpose of my follow-on work has been to round out and supplement perspectives that had initially been collected.

With just 10 OASPA publisher-members responsible for over 80% of OA output in 2021 (reported in OASPA’s end-2022 blog) it is easy to perceive that open access works in a fairly uniform way. However, there are thousands of scholarly journals, scholarly societies and platforms that we miss learning from when we focus on the biggest ‘market’ players.

Although the remainder of my post will focus on inputs where I felt I learnt the most, I should note that there was unanimous support and plenty of enthusiasm for OASPA’s efforts under the banner of the ‘OA market’. The background reports (OASPA’s 2021 issue brief and reflections on the ‘OA market’) were described in positive terms, and considered to be balanced, stable, well judged, thoughtful, and careful.

The rest of this post now explores and unpacks what else I heard in conversations about the ‘OA market’ with stakeholders from around the world.

It’s a big world after all

Attitudes and approaches to publishing are very different on different sides of the equator, and very different in the East compared with the West. From the perspective of someone in the Northern hemisphere, most peer-reviewed publications are produced by market forces, meaning that published content emerges via organizations that seek to drive revenues and profit (or surpluses for charitable work) from their publishing activity. The term ‘OA Market’ speaks to this world view. However, the motivation around publishing is often different for those based in the Global South and/or those with different perspectives, particularly those where publishing is not taking place in English.

So, before we debate the sentiments around an ‘OA market’, here are some thoughts from my conversations that challenge the (predominantly) North Westerly view of (OA) publishing:

1. Publishing can be a cost rather than a revenue/profit source

A common and headlining theme I heard about is that journals do not have to make money; they can exist as a public good without the aim of turning a profit or surplus. This is as true in Far-East Asia and the Indian subcontinent, as it is across both Africa and South America. Not-for-profit publishing platforms can and do provide infrastructure and solutions to journals across large parts of the Global South. This fact is not often in the general collective consciousness of those who work in scholarly publishing in the North/West of the world.

2. Wide access is being achieved in ways that are not always recognized

There are differing forms of open access and/or wide access that already exist in many instances of scholarly publishing.

- In Bangladesh many journals run “on donations” with content freely accessible.

- In India practically everyone who needs to can access local paywalled journals because of the low pricing involved.

- In China the online version can often be free to read while the print version costs money.

- In Africa there are local journals that charge a very small cost-recovery fee in return for open publishing.

- In Japan wide access that is practically tantamount to (bronze) open access is already achieved across ~ 3000 journals – many tied to local scholarly societies. These are distributed by a platform supported by the government.

- In South America a non-commercial meta-publisher way of open access publishing dominates, as can be seen with the examples of digital libraries like SciELO (Scientific Electronic Library Online), La Referencia and Redalyc.

Sure, these approaches to scholarly publishing may not, in all cases, deliver 100% open access (with hallmarks of OA such as re-use licensing terms and paywall-free criteria), but the point is that wide accessibility to published scholarly content is being achieved in many regions.

What could we learn or incorporate from these approaches in considering a successful global transition to full OA? And also, would we apply exactly the same transition requirements as urgently to these bodies of scholarly work as we might to paywalled journals of the North operating on subscription or hybrid models?

Finally, what effects would be faced (by journals/platforms that do not operate with a “market oriented worldview”) in a global transition to open access along ways directed by the ‘market-oriented’ North/West?

One person said to me that the most important thing was for “scholars to have access to all the content they need” and for humanity to be able to drive “the best value” out of published scholarship.

3. APCs and OA are (not?) the same

No, of course they are not. There are routes to open access that involve no Article Processing Charges (APCs). But across the conversations I had, awareness of this was limited, and the fact that OA of the final published version does not necessitate an APC is not well established. In many places OA and APCs are seen as one and the same, and talking about open access means talking about APCs. “We are learning from Europe” I was told.

For instance many African journals now rely on the APC model although quite often the fees charged are on a cost-recovery basis, and represent “a completely different ballgame” to the US $2-3000 APCs that many in the North West will be familiar with. Granting APC waivers are “unaffordable” for journals that may charge publication rates of as little as US$50 to 500.

4. How can libraries focus on content acquisition and (OA) publishing?

When discussing the money flows that might sustain OA publishing as a possible alternative to per-article charges, some conversations pointed to a repurposing of library budgets. However, across several conversations I also learnt how many libraries in regions outside of Europe do not routinely have budgets for supporting (OA) publishing. Library support of OA publishing is increasingly a norm in Europe. However, libraries in some parts of the world do not think of their role as being to enable or support OA publishing at all, and many have no budget to do so. With institutions and libraries at the heart of research communication, we need to consider the variable roles of the librarian in a range of countries in the context of any global transition to open access.

5. Pricing is a huge problem

Affordability is a real challenge with APCs “distancing access to most, especially in developing nations”. From one country I heard, “Waivers are a charity; why can we not pay in our own way with our money… why is there no compromise on price?”. From another country I heard “please cap APCs at US$500”. From yet another it was “Cost is real, but price is unreal”.

There was a strong sense of many stakeholders I spoke to feeling a sense of unfairness and exclusion, with local scholars unable to contemplate publishing OA unless funded by the likes of the Bill & Melinda Gates foundation “who will give the thousands needed for OA publication”. We need “more responsible Gold OA practices” I was also told.

Transformative agreements and Read & Publish/R&P deals came up in roughly a third of the conversations, and here, too, I picked up a level of concern. With the subscription model came ‘the big deal’ and “TAs are just a bigger deal”, I was told. There were concerns with transformative agreements not just from the affordability perspective, but also because they open the doors to OA publishing in an unequal way, favouring scholars at well funded, research-intensive institutions in certain regions.

In fact, I was told that OASPA could do more to overtly address the harmful consequences of R&P agreements which entrench the APC approach and are exclusive in nature. There were clear requests to remove the economic barrier for researchers altogether… “truly equitable OA would involve no money exchange and no transactions”.

6. “Brain drain” and (Western) market gain

Journal ranking and impact factors are (still) the “holy grail” to many scholars in the East and the Global South. The Global North is waking up to the fact that prestige and reputation are themselves a market. Similarly, the North/West of the globe has more awareness of practices like DORA. However “ranked journals” are seen as hugely important by many scholars in other regions.

From every conversation outside of the US I heard about “brain drain” from local journals in favour of prestige chasing in “ranked” and “international” titles. I heard about how many of these journals are not indexed by the large indexing giants of the North/West. Emotions ranged from puzzlement to anger to helplessness at the non-indexed status of many regional titles despite best efforts being made. The point about non-indexing of regional journals in places like Scopus and Web of Science was covered by voices across three different continents. The flip side of this position is that indexers are tasked with quality assurance, and there often isn’t a shared understanding (or agreement), across world regions, of what the parameters are, or should be. This phenomenon means local journals lose regionally relevant work – such a perverse outcome considering the purpose of (open) scholarly publishing.

Compounding the issues of a “brain drain” of regional work away from local journals and the non-indexing of regional titles, there were linked concerns about commercial players increasing market share via acquisition of local journals, and a commodification of regional solutions and networks in developing countries. “Local prices one day, international [unaffordable] pricing the next” was an outcome I heard about.

The profile and capacity of local journals needs to be built up, and it is clear that OASPA will need to continue work in this space. In some cases, more conversation and mutual consensus may also be needed about what constitutes quality.

7. Equity first for better health and diversity

An area of focus for OASPA emerging from the ‘OA market’ workshops in 2021 was to support increased community representation in publishing governance. However, I was told we needed to be much clearer about this, and that this should mean not just greater representation of those in community-based roles, but also ensuring representation and meaningful engagement from people based in different world regions who will bring a greater variety of views. Considering both a diversity of roles as well as people will help ensure we do not end up with community representation from just one global region.

OASPA feels we will need to explore the theme of community representation more carefully to consider and scope what the most valuable next steps need to be in this work around publishing governance.

A related line of thinking around diversity and inclusion was a challenge to OASPA to focus specifically on making things equitable in (OA) publishing. To build equity in open access, equity in APCs and other pricing approaches – equity so that all who want to can participate and publish OA, because: “Where there is equity, diversity automatically follows.”.

OASPA is resolute that a transition to full OA should accelerate equity rather than amplify inequity. Transitioning to full OA should also increase rather than decrease access to OA publishing. In 2023, OASPA will focus far more closely on equity in OA publishing.

So, what next for a healthy ‘OA market’?

I write this post just a few weeks after OASPA’s end of 2022 report revealed around 20x growth in OA articles published by OASPA members over the last decade, with output highly consolidated. This re-affirms issues that set the tone for OASPA’s ‘OA market’ effort in the first place. There is a need for continued work on health and diversity in open access.

My conversations with stakeholders outside of Europe boiled things down to the fact that open access is about sharing knowledge and providing access to OA publishing in an equitable way. The market is a circumstance rather than a principle. Once we accept these facts we can start to unpack the debate about the term ‘OA market’.

Look out for next week’s post about the market / anti-market debate in open access, and to read about what’s next from OASPA for a more healthy and diverse economic system.

Wishing you a happy and healthy 2023.

Acknowledgements

Sincere thanks to the following wonderful individuals who reviewed OASPA’s 2021 issue brief and reflections on the ‘OA market’ and shared thoughts and inputs over email and/or in conversation:

Name | Role | Affiliation | Country |

NV Sathyanarayana | Chairman & Managing Director | Informatics India Ltd | India |

Rebecca McLeod | Managing Director | Harvard Data Science Review | USA |

Ella Chen | Managing Director, China and East Asia | Royal Society of Chemistry | China |

Susan Murray | CEO | African Journals Online (AJOL) | South Africa |

Tieming Zhang | President & Editorial Department | Society of China University Journals & Beijing Forestry University | China |

Ren Shengli | Executive Editor | Science China Press | |

Abel Packer | Co-founder & Director | Scientific Electronic Library Online (SciELO) | Brazil |

Arnold Mwanza | Regional Librarian, East Africa | The Aga Khan University | Kenya |

Jasper Maenzanise | Institute Librarian | Harare Institute of Technology | Zimbabwe |

Peter Suber | Senior Advisor on Open Access + Director | Harvard Library + Harvard Open Access Project | USA |

Amanda Marie James | Associate Dean, Diversity, Inclusion, and Community Engagement | Laney Graduate School, Emory University | USA |

Haseeb Irfanullah | Consultant + ‘chef’ + associate | Independent Consultant + Scholarly Kitchen + INASP | Bangladesh |

Devika Madalli | Professor, Documentation Research and Training Center (DRTC) | Indian Statistical Institute | India |

Kazuhiro Hayashi | Director of Research Unit for Data Application | National Institute of Science and Technology Policy (NISTEP), Japan | Japan |

Chris Marcum | Assistant Director for Open Science and Data Policy | White House Office of Science and Technology Policy (OSTP), USA | USA |

Thanks are also due to Rob Johnson from Research Consulting for work on the 2021 OA- market workshops, related documents, and for helpful conversations over the second half of 2022.

Read The ‘OA market’ – what is healthy? Part 2 (January 31, 2023) here